The Life and Scribbles of Saul Steinberg

By Grace Roberts

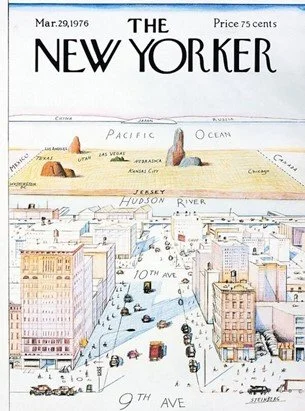

“I am a writer who draws.” By his own self-description, Saul Steinberg is an artist who wears many hats. His most notable role is as a cartoonist, one who has spanned so many years and disciplines in the art world that it would be impossible to limit him to one title. You may have seen his scribbles on the cover of many a New Yorker magazine, his most famous being “View of the World from 9th Avenue,” a piece which playfully comments on New York’s superiority complex. But his work is not confined only to magazine cartoons and commentary, and I believe his life and influence on the art world to be a worthy story, one worth telling.

“View of the World from 9th Avenue,” 1976.

The appeal of Steinberg’s illustrations isn’t hard to understand—his style is buoyant and abstract, and it’s playful but never feels like kid stuff. There’s a certain curious wonder that you tend to experience when flipping through his doodles, and once you’ve seen one you can’t resist delving into his portfolio to see what other kinds of fantastical images he can conjure up. Spanning an impressive range of artistic disciplines, Steinberg’s work has been featured in some of the world's most prestigious museums and exhibitions, both during his heyday and posthumously, and though he’s most known for his almost 60 years with the New Yorker, his legacy extends far beyond the household magazine.

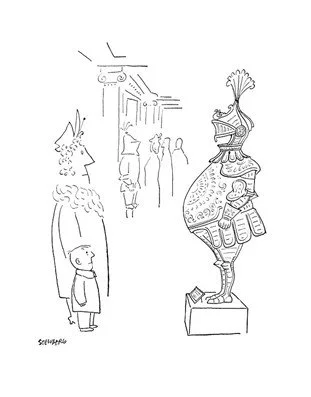

New Yorker on February 3rd, 1951.

Steinberg was born in 1914 in Romania, and grew up in what he calls “a Turkish Delight manner” referencing the intersection of Western and Ottoman thinking and styles at the time, something which came to be heavily influential in his work as an artist. However, it became impossible for Steinberg to remain in Romania after politics became increasingly anti-Semitic, and he was forced to leave his studies at the University of Bucharest and transfer to the Politecnico in Milan. Several years later when Fascist Italy enforced anti-Semitic laws, he was arrested for a month, then was forced to flee to Portugal, where he managed to get on a boat headed for the United States. Steinberg had to create a fake stamp on his passport to board the ship, but this doctored passport did him no good when he arrived at Ellis Island, and he waited in the Dominican Republic for a year before he acquired his visa. These events became an inspiration for his book “The Passport,” a series of pieces compiling both sketches from his travels and ‘travel documents’. During his time in the DR, he began drawing for the New Yorker magazine, and they were able to aid him in expediting his visa and entering the United States in 1943.

A Jell-O advertisement from 1953.

Steinberg is exemplary for his flexibility and scope within the art world; he has moved through countless modes, forms, and schools of art, from designing wallpaper, sets for the stage, advertisements for major corporations, to sculptures and collages far outside of his realm of cartoons. He’s quoted as saying, "I don't quite belong to the art, cartoon or magazine world, so the art world doesn't quite know where to place me,” which is an apt assessment of his impact. His work spans different contexts and periods of tumultuous world history, but throughout all his many forms and conditions, his style remains simple and iconic, recognizable regardless of whether it’s in a magazine or museum.

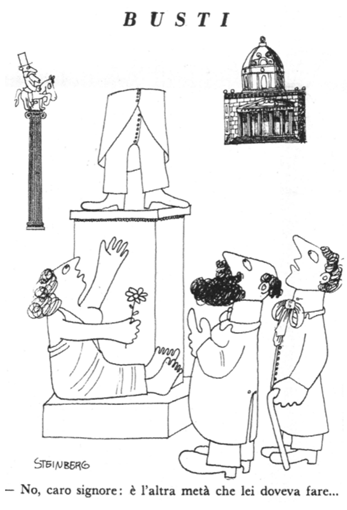

A cartoon from 1937 that translates to “No, Dear sir. It’s the other half you were supposed to make.”

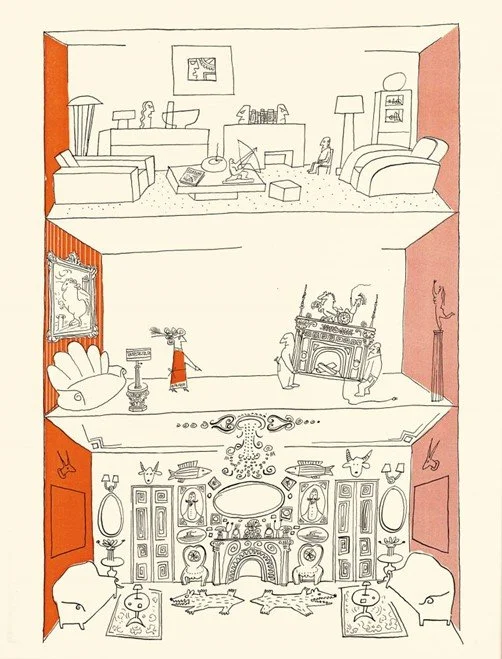

The most appropriate word to encapsulate Steinberg’s style is whimsical. There's an airy, sparse quality about his drawings that is slightly absurdist, always leaving a little bit to the imagination, as if Steinberg wanted his audiences to fill in the rest themselves. Many are downright fantastical. His most basic illustrations can only be described as doodles—snippets of men seated at a bar, women walking their dogs, and art-within-art. Much of Steinberg’s illustrations are heavily inspired by Cubism and line-drawing, styles popular in 1940s Italy, drawing scenes of sculptures-gone-wrong and landscapes reminiscent of Greco-Roman times of old. Still others reflect the culture in the US with mid-century modern influence, and a Mad Men-esque aesthetic. As he studied architecture in Milan, albeit for a short period of time, his illustrations for catalogues and lifestyle exhibitions were masterful, the interior design eccentric. His drawings make the mundane interesting and the absurd even more comedic, challenging what audiences might deem as silly in what is actually highly regarded art.

From a catalogue at “An Exhibition for Modern Living” at the Detroit Institute for the Arts.

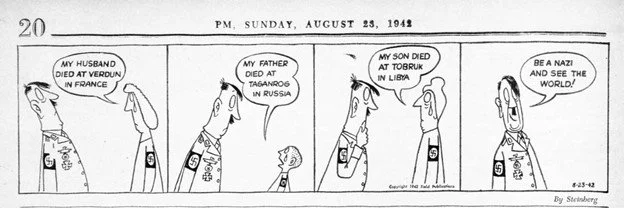

Steinberg worked for the New Yorker in arguably their most popular period, and the magazine is still known worldwide for their cartoons. Working in the magazine during this critical point in history meant many of his cartoons were politically charged, some more general and others relating to what would have been a time of great upheaval during the Second World War. Having won over editor Harold Ross with his work in the New Yorker, he was offered both US citizenship and a commission for the US Naval Reserve and proceeded to spend the wartime years traveling the world and creating pictorial propaganda for the Office of Strategic Services’ Morale Operations division. He drew upon his own experience in immigrating to the United States to inform his work, creating cartoons that explore hardship and often tragedy, never trying to use humor to glaze over the past, but to instead provide a lens with which to view it in a lighthearted manner. He was no stranger to the realities of the world, which made his grip on what makes art worth creating so strong that its relevance is still present today. This is incredibly important when recognizing that he considered himself to be both writer and artist, having to constantly bridge the gap between text and image, and the most effective result often being to simply combine the two.

Anti-Fascist cartoon published in PM, 1942.

Being a cartoonist means wrapping up a singular issue, opinion, or event into one small scene, usually with some form of irony or comedic twist. Recognizing the specificity and complexity of what appears to be such a simple piece of art is taken for granted—cartoons date back to the Middle Ages, and have always been prevalent in politics, in particular. While the umbrella of what constitutes a cartoon is actually quite broad, cartoons as a form of art and design in magazines is a specific and regulated niche. If we consider the early history of the United States, for example, cartoons will likely bring to mind Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” illustration, used to make a political statement about statehood in one simple drawing of a snake. Similarly, we can understand cartoons to not only have a humorous or entertaining edge, but an educational one too.

Many people have in fact debated whether or not we can classify the work of Steinberg and his cartoon contemporaries as “artists,” for cartoons are often regarded as a sort of gray-area, not quite “high art” but not meaningless doodles either. However, this question seems obsolete when we consider not only how Steinberg’s cartoon artistry continues to bring joy to people long after his death, but how popular cartoons continue to be in the media.

Untitled, 1948.

Steinberg’s ability to simply be an artist, nothing more and nothing less, is perhaps his most admirable quality and an undeniable factor of his legacy. While there are specific niches for which he is known and pieces for which he has been honored, he remained loyal to the idea that his job was to create art regardless of the form or medium in which it manifested. His style remains iconic and recognizable, and I’ve never grown tired of it because just when I think I’ve seen the funniest or most bizarre one yet, I become aware of some new doodle of a man carrying what appears to be a rock (which is actually Steinberg’s thumbprint) and am thrown back into his world of impossibilities. Steinberg does not distinguish between high and low art, a quality which I continue to notice in his work and think is worth appreciating more in the rest of the art world today. Steinberg’s work will continue to challenge artistic tradition, and his legacy for bringing the world whimsy without sacrificing meaning is one I imagine will live on forever.

ST. ART Magazine does not own the rights to any images used in this article.