Theatre Review: Vanya

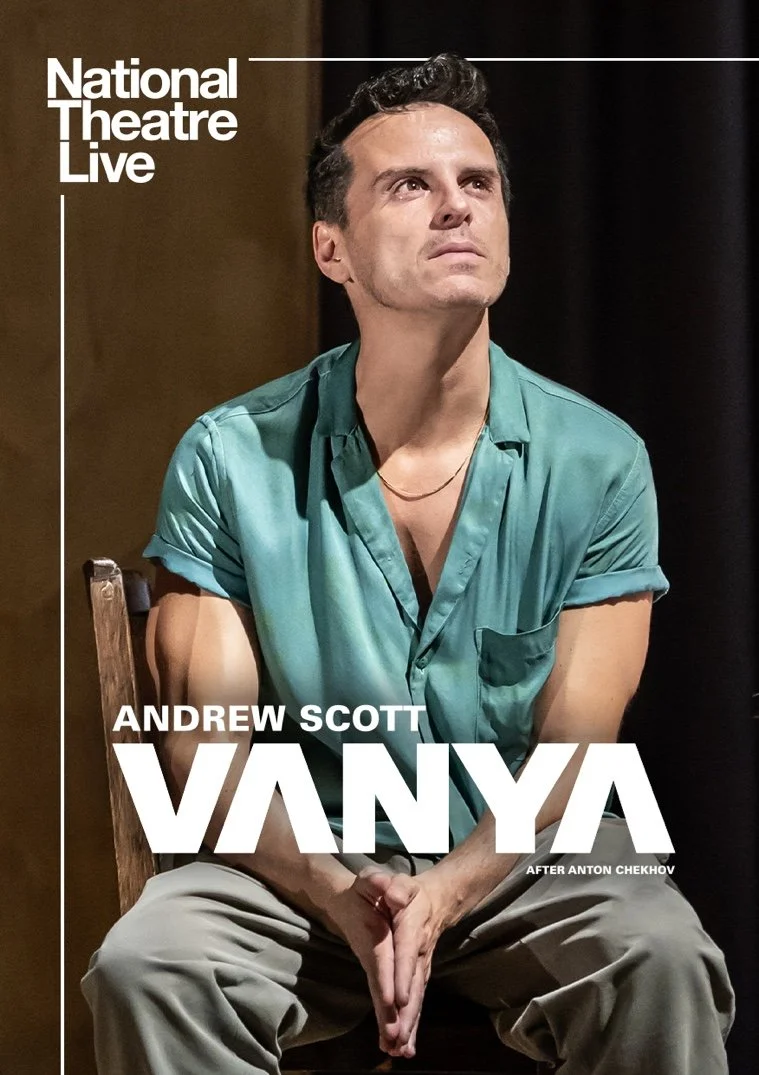

Vanya

Starring Andrew Scott

National Theatre, London

15/9/23 - 21/10/23

Adapted by Simon Stephens from Uncle Vanya by Anton Chekhov

Directed by Sam Yates

Designed by Rosanna Vize

Review Based on National Theatre Live Streaming 2024

Review by Noor Zohdy

A disparate, domestic scene. Andrew Scott, the sole actor, walks on stage, flicks on a light, runs a tap, and lights a cigarette. Capturing the will o’ wisp haunting vividity of Chekhov’s theatre, Scott’s performance was exquisitely done. It was miraculous, seeing characters unfold before your eyes. One moment, he was drunkenly stumbling towards the door, the next he was leaning out the frame, pointing the way, looking with wistful, laughing eyes up the stairs. One moment, he stared vacantly at an empty bottle, the next, he was looking at it in helpless silence, with both hands seeing the long-gone person who once held it. The transfixing poignancy of words to empty chairs, kettles running untouched. I saw people become memories, one second looking at an empty chair, another looking at the abandoned swing as it swayed, abandoned. With its frayed edges, its endless, unravelling quality, it felt like a portrait of memory itself. Voices and lives dashing around the fringes of an ebbing, vanishing centre. At one point, Vanya sits and watches piano keys play on without him. It was his sister’s piano before she passed. He sits at the edge of the seat as if alongside her and smiles, playing keys alongside her invisible fingers. Half a minute sitting there and then all the characters stream back in, the spotlight shifts. But the lyricism, the whispers of unfinished songs, memories, and flickering voices scintillate through all the discordance, chaos, and despair. Beyond the empty chairs, the constant pictures of vacancy, absence, and hopelessness, there drifts something complete. The play rushes on, reaching for shadows vanishing out of sight, looking at ripples of one face, of one fragmented truth, as laughter bleeds to tears, and moments of the hardest reality flake away beyond human reach. But there hangs always that touch of Chekhov in which the gravest despair lifts your mind with something like expectation.

The play comes to a close and Sonya delivers her heart-stirringmonologue. ‘One day we will understand’, in our final moments ‘we’ll understand’, ‘we’ll understand’ she says as she rests her head on Vanya’s knee. ‘Haven’t you noticed if you are riding through a dark wood at night and see a little light shining ahead?’, ‘I see no light ahead’ Michael once said. Yet, the overcast lights, the escaping, inaudible realities that shadow this haunted play, this spectacle of the human mind, align for a single breath as Scott stands up and faces the audience: a light between the trees, the empty chairs, the kettle whistling alone, seconds turned to memories and memories turned to absence. And then familiar and distant, an unspoken realisation like something half-forgotten, long-lost, the piano keys playing on untouched, and perhaps we nearly understand, we catch a refraction of the light between the trees, that ceaseless flush of expectation catches breath and we nearly understand: a flicker of the final moment Sonya promised, Michael’s vision between the branches, and Scott leaves the way he came, finally, he switches off the light.