Bare Feet on Cold Walls With the Bedside Table as Your Only Friend: Melancholy and Loneliness in the Films of Chantal Akerman

By Jay Martin

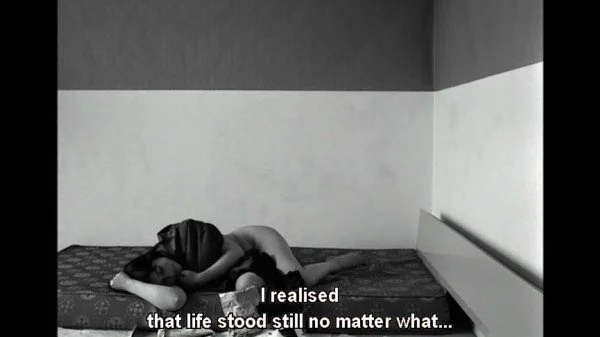

From Je tu il Elle, Chantal Akerman (1974)

Sitting in lecture theatres or walking supposedly beautiful cobbled streets; getting caught in the rain or lounging on the beach in the sun; writing essays hours before they are due or drinking perilously night after night after night. I try, with all these things shaping my material reality, to hold onto whatever came before it. The ‘past’ or my ‘childhood’, or whatever. I don’t remember it. I just try to reminisce, cling on to anything I can from that time. But I don’t remember it. Those memories have faded into the unfamiliar places which have come to envelop me this past year. I can walk into Waterstones and buy a postcard for the town I live in year round. There are no postcards for Barrhead, no postcards for Paisley. The sense of unfamiliarity, of outsideness, grows. I doubt I’ll ever be as chummy with St Andrews as I am with my hometown. And I question, truly, if I am even meant to be. I’m not stuck here. After four years I can leave, go anywhere else. But I should be happy, right? I shouldn’t feel permanently out of place. I shouldn’t have to respond to the question “how are you doing?” with “I’m fine”, when in reality I so often feel scared and alone rather than enthusiastic and thrilled. I ought to be here, but I don’t know if I want to be.

I scribbled that in the back of a notebook at some point last year before tearing out the page and throwing it in a drawer. I wasn’t doing so well at the time. When I got home for the summer break, I went through all the papers I’d had strewn across my room over the course of the year and I found this one to be both laughable in its self-pity but also deeply relatable. Things had gotten better since I arrived home from St Andrews. I was happier, overall. I’d stopped drinking. I was continuing to foster relationships which were very important to me. And it’s natural for the human brain to try and make vague links between things. Damning St Andrews as the cause of all my problems was, dramatically, what I did. I kept the page though, because whilst it was easy for me to dramatise things, something true flickered beneath that scrawl of self-indulgent anguish. I filed it away in my (ironically cheery) otter notebook, and this was around the time I first watched Je tu il Elle.

From News from Home, Chantal Akerman (1977)

The films of Chantal Akerman have regularly been called uniquely relatable, deeply melancholic, beautifully sombre. I’m not here to argue with those analyses, as too many have. A feminist, certainly, and a great artist, undeniably, but there is no hidden optimism beneath Akerman’s films. No bittersweet moral to uncover. Akerman was, fundamentally, a postmodernist filmmaker, a Bergsonian one at that. “Instead of attaching ourselves to the inner becoming of things, we place ourselves outside them in order to recompose their becoming artificially. We take snapshots, if it were, of the passing reality… We may therefore sum up … that the mechanism of our ordinary knowledge is of a cinematographical kind” (Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, 1907). Cinema fulfils, simultaneously, the intellect’s ability to understand the notions of being, inertia and immobility, and intuition’s ability to recognise the concepts of becoming and of reality in flux. There is no hidden meaning in these films. What Akerman sees, Akerman shoots. What Akerman shoots, Akerman means. This is what alleviates Akerman to the auteur status she now receives. This is what gives her the key to unlock an unmatched relatability across her body of work. Films like Je tu il Elle and News from Home don’t really end, they simply run out.

Je tu il Elle hit me like a truck when I first watched it. It is eerie to watch a film hold a mirror up to you. Akerman poignantly explores isolation, meaningless relationships and feelings of drifting senselessly from one place to the next. The first third of the film utilises a single setting, which is shot from every angle in different lighting, making it feel like a different space with every new shot. But it never is. Julie, played by Akerman herself, is alone in her room. Nude for most of the shots, she lounges around, rearranges the furniture, eats sugar from a paper bag. There’s a resounding sense that the comfort Julie ought to be enjoying in her own space is, in fact, repulsively undesirable. She ought to be there, but she doesn’t know if she wants to be. The subsequent two acts follow Julie as she engages in meaningless sexual endeavours, first with a random man, and then with her ex-girlfriend. Both are unfulfilling. The latter is more sensuous and engaged than the first, but both end with Julie leaving. The scene Julie and her ex-girlfriend share in the third act of the film is remarkable for the time period, being, to this day, one of the longest sex scenes between two women in cinema. This is a recurring quality of Akerman’s films, but she offers no false pretences. Her feminist filmography frequently pushes the boundaries and transgresses against the cinematic laws of the time, but it is the melancholic isolation which pervades when engaging with her work. These, inevitably, go hand in hand. Akerman famously, whilst cooly smoking a cigarette, said “With me, you see the time pass. And feel it pass. You also sense that this is the time that leads towards death. And that’s why there’s so much resistance. I took two hours of someone’s life.” The crushing feeling which comes as Je tu il Elle peters out, as Julie will inevitably return to that room we saw her in for the first third of the film, as the cycle will start again, is achieved, in part, by the 20 minute sex scene which precedes it. All that time, for Julie and us, means nothing in the end.

News from Home is a film populated by ghosts. We will never know anything about the hundreds of people who appear on the screen. We will never know what they desired, how they were loved, the hardships they faced, their familial complexities. We will never know the unique meaning of Home to them. We will never even know their names. These are stories which exist, they are merely lost. Images live on where stories do not. Recognised but not seen. Acknowledged but not remembered. The film consists of several long shots of various environments across New York City, accompanied by Chantal Akerman reading letters sent to her from her mother back home in Belgium. By 1977, living in New York, Akerman was feeling a deep sense of lost time and loneliness, and made News from Home as a record of that. The film is stunning, my absolute favourite of all time. No other film has ever made me tangibly miss things in the way News from Home does. I miss the past, I miss the future, I miss my family, I miss my cat, I miss making friends, I miss my boyfriend. I see several familiar faces in St Andrews, be it in tutorials or lectures or ‘Pret’, and I don’t know what they desire, what they love, what they miss, but I am almost certain they do. These feelings are common, perhaps the most common. This is why I sob every time I watch News from Home. It’s sad, yes, but it’s also me, and it’s also you. It’s Akerman and it's all of us. Gilles Deleuze said that “Time, in order to become visible, seeks bodies and everywhere encounters them, seizes them to cast its magic lantern upon them” (Gilles Deleuze, Proust and Signs, 1964).

I am now back in St Andrews, and relatively happy to be. I was a tad dramatic in that note from last year, but I don’t think I was entirely wrong. I merely had things the wrong way around. The films of Chantal Akerman are startlingly relatable. There is no other filmmaker with a body of work so resoundingly tangible, both universal and deeply intimate. As noted, Akerman is not one to spoon feed the viewer lessons on life. She, instead, holds up a mirror and what one chooses to do with that is down to them. For me, certainly, Akerman allowed me to stop chasing lost time, and to simply let it “become visible”. Let the future be imbued with the past. Let the self be imbued with potential. The isolation I felt was not a product of St Andrews. Not a product of my environment. I let the four walls of my present take control of my mindset. But as Proust said, in a work which Akerman herself would go on to adapt, “The only true voyage of discovery… would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes.” (Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time: Volume V, 1923)

From News from Home, Chantal Akerman (1977)

Works Referenced

Bergson, Henri, ‘Creative Evolution’ in Henri Bergson: Key Writings, (eds.) John Maoilearca and Keith Ansell Pearson (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014)

Deleuze, Gilles, Proust and Signs, (trans.) Richard Howard, (London: Continuum, 2008)

Proust, Marcel, In Search of Lost Time: Volume V, (trans.) D.J. Enright, C.K. Scott Moncrieff, and Terence Kilmartin (New York City: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1996)

ST.ART does not own the rights to any images used in this article.